Posted 7/15/2015

Updated 7/24/2015

This story was originally published in the December 1976 issue of The Lap Times, the AFM’s official newsletter. Two-stroke fans might get a kick out of it.

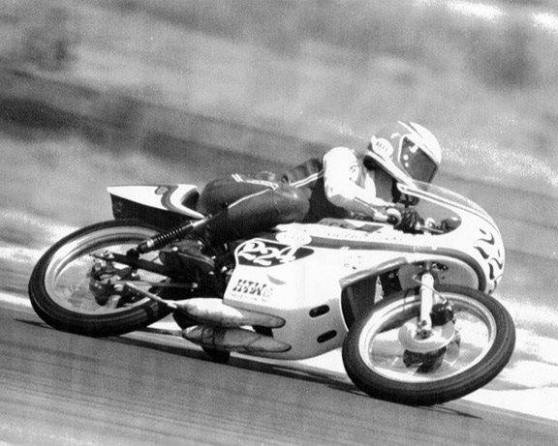

Philippe DeLespinay at speed on the Garbage Can Special. Photo from (I think) Ken Mullins collection.

What is it, exactly? Some people think it’s a Yamaha TZ125, but Yamaha didn’t have a TZ125 in 1976. The eighth-liter race bike from Yamaha was a TA125, an air-cooled 2-stroke parallel twin. The TA125 was basically a hopped-up version of the RD125 street bike. Perhaps the GCS is a TA125 with a aftermarket water-cooling kit from somewhere in Europe. The bike has entered the AFM races as a “Mifuni 125,” racing in the 125 GP class. The owner calls it the Garbage Can Special. Whatever this bike is, it’s become the scourge of the 125 GP class, winning the last three races at Ontario Motor Speedway in 1976.

Water cooling is a big deal for a 2-stroke. Jetting an air-cooled 2-stroke motor is tricky. Jet it too rich and it doesn’t make much horsepower, jet it too lean and it overheats and seizes, or burns a hole in the piston. With water cooling you can watch the temperature gauge to guard against too-lean jetting and consequent overheating.

Intrigued by what appears to be a very different motorcycle, the Lap Times talked to the owner-rider, Philippe DeLespinay, to find out just what the bike is. It’s not a early-release Yamaha TZ125, nor is it a Yamaha TA125 with a water cooling kit. It is a well-thought-out, superbly-executed, home-built Grand Prix race bike. Practically everything on the bike is handmade or a modified production piece.

The center of attention is, of course, the engine. The crank cases are from a Yamaha TA125 but have been altered to accept different bearings with special retainers. The crankshaft also begins life as a TA125 part, but Hurley Wilvert does a number on it, reducing the overall diameter and fitting different crank pins and big-end bearings. The gearbox is still a 5-speed unit but some of the gears come from England, and all have been given a 5-degree chamfer to reduce weight and make engagement smoother.

The top-end is where things really get different. It’s still a parallel twin, but with a one-piece cylinder and water jacket, unlike the two separate cylinders of the TA125. The cylinder was designed by Philippe and sand cast in France, from where Philippe hails originally. The liners are cast iron, pressed in at a temperature of 400 degrees Centigrade. The bores as not chromed, as it’s easy to obtain cast iron sleeves and have them honed to match the pistons in case there is a drastic engine failure. The porting is typical piston-port style, developed by Philippe and Wilvert. Compared to the standard TA125 porting, the timing is less radical in the intake and exhaust and more radical at the transfer ports. Wilvert also built the expansion-chamber exhaust pipes, which are much shorter and fatter than TA125 pipes. The radiator is from a Kawasaki KR250 and the water pump, which is completely handmade, replaces the standard TA125 oil pump. With no oil pump the motor runs on old-fashioned oil-gas premix.

The cylinder heads are separate pieces that are recessed into the top of the cylinder jacket, instead of sitting on top TA125 style. The cooling fluid doesn’t pass over the heads but it surrounds them on all four sides for effective heat transfer. This feature allows fitting different cylinder heads without having to drain the coolant. This allowed DeLespinay and Wilvert to quickly try several different combustion chamber shapes during development.

That pretty much covers the engine alterations, and they work very well. The bike is intentionally run with slightly over-rich jetting yet it is still much faster than the standard TA125. The power band has been increased from 10,500 – 12,000 rpm to a very broad 10,500 – 15,500 rpm. The engine will spin to 16,000 without coming apart or seizing, and power is increased accordingly. Philippe claims the bike produces about 35 horsepower. If someone expresses disbelief at this number Philippe is quick to point out that the production Morbidelli 125s make about 37 hp, and the factory Morbidellis make nearly 40 hp.

[An aside: Morbidelli is an Italian firm that makes wood working machinery, but the 1970s owner was a motorcycle race fan and he also made a small number of 125cc race bikes for FIM (European) Grand Prix competition. Morbidelli is the only class-winning motorcycle in the long history of world championship racing that was not built by a motorcycle manufacturer, earning the 125cc championship in 1976 and 1977. The bikes and parts were nearly impossible to get in the U.S.]

You would think that having a reliable engine with more horsepower than anyone else in the class would satisfy most people. You could stuff it into a stock Yamaha TA125 chassis, hang the radiator somewhere near the front and have an instant race winner. Philippe and his pals don’t work that way – along with the custom motor are a host of chassis improvements. The frame began as a Jack Machin model from England, and then was altered to Philippe’s specs by C&J Frames. The front fork is a Cerianni unit with its internals replaced by Wilvert-developed pieces. The front wheel is built up from a machined magnesium hub carrying two unplated 2025-T6 aluminum brake disks. Brake calipers are from a Honda 500 four. The tires, front and rear, look like standard Dunlop K-81s, but are made with a racing compound on a racing carcass in Dunlop’s French factory, obtained through Harry Hunt.

Why does Philippe call it the Garbage Can Special? He likes to pretend he got many of his parts from the disposal bin. The original crankcases, brake calipers and radiator, maybe, but not much else.

It all adds up to a lot of hard work. Fortunately Philippe has had some help along the way. HTW Racing (Hurley Wilvert’s company) and California Cycle Center, both of Santa Ana, CA, have provided sponsorship. Harry Hunt donated tires and Bell Helmets has helped out. Even with the aid it’s clear that an enormous amount of time and talent has been spent on the project, and one begins to wonder, why so much effort for a few club race wins? Perhaps there will be a water cooling kit sold in the future. But talking with Philippe you get the feeling that he is not doing all this just to sell water-cooling kits to Yamaha TA125 owners. He likes to build motorcycles then win races riding them.

There is another possibility: the 125 project may have been a warm-up for the 250cc bike they are planning to build. The GCS is pretty trick and a fast 125cc bike, but wait until you see the 250cc version.

Postscript: To my knowledge the 250cc version of the GCS was never completed. Philippe is active on Facebook so perhaps he can add some comments to this page. According to sources on the internet Yamaha released the water-cooled TZ125 in 1979, making the GSC a bit less special. Still, Philippe got a three-year head start.

The TZ 125 that was released in 1979 was indeed water-cooled, but was a single-cylinder machine which was not at all competitive against the usual twins in the category (still mostly Morbidelli / MBA plus factory Garelli, Minarelli …. ) Maybe a simple and cheap machine for a rookie to start racing, like the equivalent Honda MT 125 . It was not until 1988 that the FIM limited the 125cc class to a single cylinder for international racing, and by then the TZ125 was of course obsolete.

Yamaha can be sneaky that way. When I see “TZ” I think parallel twin for the smaller displacements, in-line four for the larger bikes. They should have used a different model name. Thanks for the clarification.

I have put a link to this blog entry on a french forum that Philippe (de Lespinay) often contributes to – hopefully he will see it and maybe comment. Oh, and the reason why he didn’t continue with the GCS project is that through a personal friendship that he developped with Signor Giancarlo Morbidelli, he was entrusted for the 1977 season with an ex-factory Morbidelli twin with which I think he fairly much cleaned up the californian 125cc scene the following years.

Lots of fun memories there… most of it is true, some is a bit of fantasy… 🙂

One thing is however, very sure: that little bike was no garbage, and was very competitive with everything that was available then.

Philippe sent me a message and a photo of the GCS. I added the image to the end of the page. The message started an exchange I’ve copied below:

Philippe de Lespinay: Paul, thanks for posting the story about my home-built little rocket in your blog. At the time, I was working as a project engineer for the Cox toy company in Santa Ana, I designed anything from model airplanes to slot cars to model trains to gas engines!

I did not have any money and we built this thing on pennies with the help of my friend Hurley Wilvert who deserves lots of credit for ideas that worked, and worked well, and his impeccable workmanship.

Just this month, my wife and I had the Wilverts as visiting guests in our home after many years of being strangers, and we had a great time reminiscing those days, when hardship was normal and no one complained, we just dealt with it!

You will be pleased to know that the little bike did survive, and was the subject of a cosmetic restoration about 20 years ago, and is now on display in a private museum in Los Angeles… I plan to get it running again sometimes next year.

Marc Wayne Salvisberg: Why do I hear the theme song of Flight of the Phoenix? lol! “What do you mean you’ve never designed a full sized motorcycle? Oh, it’s not really full sized. Ummm, OK, it’s great.” 🙂

Kaming Ko: I remember this bike and a beauty it was and still. Great job.

Carry Andrew: Love the disc brakes.

Philippe de Lespinay: Uncoated aluminum. Everyone told me that it could not work. They worked great. Never had any galling, they were still like new after two seasons of outrbraking just about everyone in the class. Pulll harder and it stood on its nose. Used Honda CB500 master cylinder, calipers and pucks. I made the hub on a lathe, got a used DID rim from someone, laced the wheel and machined the discs from a chunk of 7075T6. Cheap and simple. Light too compared to the Yamaha drum brake. The whole bile was 173 lbs, I recall that number because it was nearly 50 lbs lighter than my TA125.

Sorry for the typos, I did not have my reading glasses… I corrected them on FB.

i have just discovered your exploits looking up information for a mba i last raced in 1985 i have just got it back to restore for vintage racing Iremember Hurley coming to Australia in the 70s

Hello Marcus,

I own a 1976 MBA of the first series. What you would like to know? Best is to contact me through my Facebook page under my name at philippe.delespinay

Regards,

Philippe